6-dimensional model of cultural analysis

Virginia Mihaela Dunitrescu in

her article Cultural Challenges Posed by E-learning in an Ethnically Diverse

Academic presented Geert Hofstede’s 6-dimensional model of cultural analysis to

identify the main cultural differences that may emerge in the process of

blended learning. She discerned few of these dimensions:

- power distance (PD),

- individualism (IDV),

- uncertainty avoidance (UAI).

The first cultural dimension

analyzed by Hofstede, power distance PD, understood as the extent to which the

less powerful members of institutions and organizations within a country expect

and accept that power is distributed unequally, has multiple “consequences” in education:

in large PD societies, where people tend to view inequality and hierarchy as

natural, all education system is teacher-centered: the educator appears as an

authoritative guru who commands respect,

initiates communication with his students, passes his personal knowledge to

them, outlines paths to follow, and appreciates order (for instance, students

are not supposed to speak up in class uninvited). The teacher’s authority is

similar to that of the father as head of the family. Since he or she is regarded

as an unquestionable source of authority, the teacher cannot be publicly

criticized, challenged or contradicted.

By contrast, in small PD societies,

which are more egalitarian, the education system is student-centered. The

teacher, perceived as a competent person, treats his students as equals, so he

expects and encourages them to think and act independently (for example, to

speak up in class, ask questions, even contradict and criticize teacher, and

finally find their own true). Hence the different way of looking at the

effectiveness of learning in the two types of cultures: in one case, the key to

success lies almost exclusively in the teacher’s hands (and depends on his

pedagogic excellence), in the other, the quality of the education process results

from the amount of two way teacher-student communication in class, and

ultimately on the student’s own merits. Virginia Mihaela Dunitrescu revealed

that very hierarchical cultures with high PD scores (e.g. Far Eastern cultures,

most Eastern European cultures) are expected to score low on the individualism

scale, whereas egalitarian (low PD) cultures (e.g. Scandinavian countries, the

US) are also the most individualistic.

Behavioral patterns in education differ

in individualistic and collectivistic cultures in terms of:

individual students

speaking up in class to express themselves in response to a general invitation

made by the teacher

VS.

individual students speaking up in class only with the

approval of their group, as spokespersons of their group, or when personally

targeted by the teacher;

students feeling comfortable speaking up in large

groups vs. small groups; weak vs. strong face-consciousness (or the importance

attached to personal reputation, based on the principle that neither the

teacher not the student should lose “face”); and acceptance of confrontation

and conflict vs. an effort to maintain harmony in learning situations.

Researchers have noticed significant differences between the attitude of

students from high and low PD cultures towards their teacher; on the one hand,

in high PD cultures such as China (PD 80), the Middle East (PD 80), most

Eastern European countries (for instance Romania, PD 90, and to a lesser extent

Poland, an exception to the negative PD/IDV correlation, whose PD score, 68, is

counteracted by its quite high IDV score, 60) the teacher is regarded as an

infallible and unquestionable source of authority, whereas in lower PD cultures

(e.g. Israel, PD 13; white South Africa, PD 49), students are more tempted to

express points of view contrary to the ones of the teacher.

Article author sad the new element of technology that interferes between teacher and student in the form of students’ access to Internet material destined for either self-study or course and seminar debates has the effect of decreasing the psychological distance between learner and teacher in more ways than one: apart from exposure to multiple and easily accessible resources, students gain access to a multitude of points of view (and sources of authority) on the same topic, some of which may be contradictory. Author distinguish that Asian students in a multicultural environment soon learn to bridge the culture gap between high and low PD and IDV by becoming more willing to express personal, critical opinions, even if they may differ from those of their group. This is totally in keeping with many researchers’ opinions about the egalitarian, democratic nature of the Internet. Another far-reaching cultural aspects – UAI - the extent to which the members of a culture feel threatened by uncertain or unknown situations. In other words, understood as a measure of a culture’s tolerance of unpredictability, novelty, uncertainty and ambiguity. In education, it can be used as an indicator of a willingness to take risks by innovating or exploring new methods of teaching and learning (characteristic of low UAI cultures) versus a preference for the safety of more traditional methods (specific to high UAI cultures).

The interesting thing is that

Hofstede insists there still is a clash between low and high UAI cultures in

terms of people’s use of new technology: at one end of the continuum, there is

wide acceptance and use of mobile phones, the e-mail and the Internet; at the

opposite end, most people are still reluctant to use them, and prefer the

security of face-to-face communication and paper printed material to avoid the

risk of miscommunication. They noticed the same distrust of emailed information

(e.g. deadlines and other important dates) as opposed to face-to-face communication.

While some of students (from such cultures as China, Indonesia, India, South

Africa) tend to act upon the e-mailed information, the typical Romanian or East

European student feels it necessary to first check and sometimes even

double-check it in a face-to-face dialogue to make sure their understanding is

correct, out of a characteristic (high UAI) fear of making mistakes.

The same attitude is noticeable when students are asked to send an assignment (e.g. a test/an exercise) via email as opposed to presenting it in class, and especially when they receive guidelines for preparing their end-of-semester projects or their dissertation papers either by email or by checking the information available on the program’s website, as opposed to discussing them face-to-face. Likewise, lectures delivered in the form of multimedia presentations using a mix of slide shows, video clips or audio portions, although enjoyed by students, must be supplemented by the teacher’s detailed explanations on the main points of the topics presented so that high UAI students may absorb the new information with more confidence.

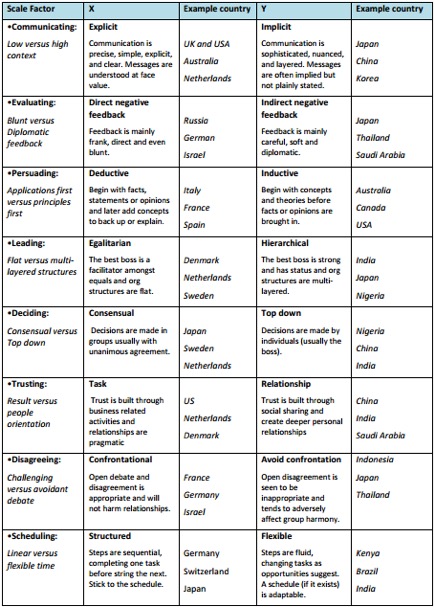

In the table below (table 1) you can see more cultural and social differences. This is Erin Meyer’s 8 different dimensions of culture map.

For the better understanding of the scale factors, there is wider explanation:

- Communicating – Are they low-context (simple, verbose and clear), or high-context (rich deep meaning in interactions)?

- Evaluating – When giving Negative feedback does one give it directly, or prefer being indirect and discreet?

- Leading – Are people in groups egalitarian, or do they prefer hierarchy?

- Deciding – Are decisions made in consensus, or made top-down?

- Trusting – Do people base trust on how well they know each other, or how well they do work together?

- Disagreeing – Are disagreements tackled directly, or do people prefer to avoid confrontations?

- Scheduling – Do they perceive time as absolute linear points, or consider it a flexible range?

- Persuading – Do they like to hear specific cases and examples, or prefer holistic detailed explanations?[1]

Troy Heffernan (2010) in research “Cultural differences, learning styles and transnational education” identify differences between Chinese and Western students, and reasons for these differences. It is apparent that the collectivist nature of the political system and the Confucianism elements of the Chinese identity have influenced teaching and learning styles in China. For example, noted that the collectivist culture in China has led to students being taught in large groups, with little tutorial or one-on-one sessions taking place (Xiao & Dyson, 1999), which in turn has impacted students’ ability to express their own opinions. Xiao and Dyson (1999) also noted a strong hierarchical relationship between teacher and student, leading to a teaching-centred learning environment. Confucianism appears to partly explain the existence of this teaching-centred learning environment. Also noted that the Confucian value of modesty of behaviour has reduced the likelihood of Chinese students questioning their teachers (Chan, 1999). Other values associated with learning in Confucian heritage countries, of which mainland China is one, include:

- Valuing theoretical education higher than more vocational education;

- Viewing learning as a moral duty;

- Hard work and effort are seen as more important than ability;

- Respecting the teacher and seeing him/her as a model of morality and knowledge (Biggs, 1996; Lee, 1996).

[1]Rawn Shah. The Culture Map' Shows Us The Differences In How We Work WorldWide https://www.forbes.com/sites/rawnshah/2014/10/06/the-culture-map-shows-us-how-we-work-worldwide/#5b0ce8385bcb